Instructor: Debasis Sengupta

Office / Department: ASU

Email: sdebasis@isical.ac.in

Marking Scheme:

Assignments: 20% | Midterm Test: 30% | End Semester: 50%

Contents

Case Study: The Challenger Disaster

1. Events and Main Points

- Jan 27, 1986 (Night before the launch):

- A 3-hour teleconference was held between:

- Morton Thiokol (manufacturer of the solid rocket motor)

- Marshall Space Flight Center (NASA design control)

- Kennedy Space Center

- Main topic: Effect of 31°F forecast temperature on O-ring performance

- A 3-hour teleconference was held between:

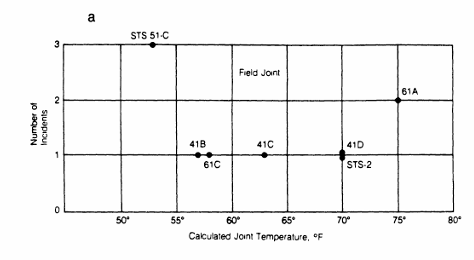

- Data Presented (Figure 1a):

- Each point = a shuttle flight with O-ring thermal distress

- X-axis = joint temperature, Y-axis = number of distressed O-rings

- Zero-failure flights were omitted, making the plot misleading

- From this “U-shaped” plot, some concluded there was no clear temperature effect

- Debate During Teleconference:

- Some recommended delaying launch until temperature was above 53°F, the lowest prior launch temperature (which had the most O-ring distress)

- Others believed data was inconclusive, though physical evidence suggested otherwise

- Roger Boisjoly (Thiokol engineer) insisted that temperature was a discriminator

- Final Recommendation by Morton Thiokol:

- Proceed with launch

- Stated: “Temperature data [are] not conclusive on predicting primary O-ring blowby.”

- Acknowledged colder O-rings become harder, take longer to seat, and thus are riskier

- Jan 28, 1986 (Launch Day):

- Challenger launched at 31°F

- Catastrophic failure occurred shortly after liftoff due to O-ring seal breach

- Aftermath – Rogers Commission Findings:

- Cause: Combustion gas leak through the right booster aft field joint

- Determined that the key analysis mistake was excluding zero-incident flights from the plot

- Including them shows a clear correlation between low temperature and O-ring failure

- Concluded that proper statistical analysis would have revealed the danger

The Challenger disaster underscores how flawed data visualization and the exclusion of critical information (zero-incident flights) led to a catastrophic decision. Proper statistical reasoning could have prevented the tragedy.

Figure 1a: Visualization excluding zero-incident flights.

Figure 1b: Correct visualization including zero-incident flights.

Main Points and Events

- Section 3 – Evidence of Temperature Effect

- Analysis of O-ring thermal-distress data shows strong statistical evidence that temperature affects O-ring performance.

- This alone could have influenced the teleconference decision before Challenger’s launch.

- Section 5 – Probabilistic Risk Assessment

- Using Section 3’s analysis as a base, a risk assessment was done for catastrophic O-ring failure.

- Under Challenger’s actual launch conditions (31°F): Probability of failure ≥ 13%.

- If postponed to 60°F: Probability of failure ≥ 2%.

- Section 5.2 – Uncertainty in Estimates

- A postanalysis prior distribution was derived for future risk assessment.

- At 31°F: mean probability ≥ 16%, median ≥ 13%.

- At 60°F: mean probability ≥ 0.004, median ≥ 0.02.

- Additional Analyses (Sections 4 & 5)

- Studied other factors:

- (a) Nozzle-joint O-ring performance (important since nozzle and field joints use the same type of O-ring)

- (b) Leak-check pressure effects

- (c) Influential observations

- (d) Possible model misfit

- Studied other factors:

- Connection to NASA Reforms

- Some work was conducted while Bruce Hoadley served on the Shuttle Criticality Review Hazard Analysis Audit Committee (SCRHAAC).

- Recommendations from SCRHAAC (1988), influenced by this analysis, received press attention and changed NASA practices.

- NASA began:

- Building a staff skilled in statistical science

- Conducting probabilistic risk assessments of major subsystems

- Purpose of Article

- Intended as a blueprint for future NASA risk analyses.

These sections emphasize how statistical analysis revealed the strong role of temperature in O-ring failure, provided probabilistic risk estimates under varying conditions, and ultimately influenced NASA’s reforms toward systematic probabilistic risk assessment.

Main Points and Events

2. Shuttle System

- Shuttle consists of 4 subsystems:

- Orbiter (crew + controls)

- External liquid-fuel tank (feeds orbiter’s main engines)

- Solid rocket motors (made by Morton Thiokol)

- Focus: Solid rocket motors because the Challenger accident was caused by O-ring failure at motor field joints

- Motors are shipped in 4 pieces and assembled at Kennedy; joints = field joints

- Similar joint with nozzle = nozzle joint

- O-rings:

- Two per joint (primary + secondary)

- 37.5 ft diameter, 0.28 in thick

- Designed to seal gaps between metal casings

O-ring Function & Issues

- At ignition: pressure + heat build → O-rings erode

- Putty used to protect O-rings; pressure displaces putty → pressurizes behind O-ring → energizes seal

- Leak test port added; pressure test raised from 50 → 100 → 200 psi

- Engine qualified to 40°F minimum operating temperature

Early Evidence of Problems (Pre-1986)

- 1977: NASA discovered field-joint rotation → casings bulge → tang rotates relative to clevis → joint gap widens

- Primary O-ring usually seals

- Secondary O-ring can lose contact → no redundancy

- Memos (1978–79): design change “mandatory” to prevent catastrophic failure

- 1982: Secondary O-rings officially classified as non-redundant

Shuttle Flights Evidence

- 1981 onward: Thermal distress observed in O-rings

- Erosion: heat burns O-ring

- Blowby: hot gases leak past O-ring

- Blow holes in putty (exacerbated by higher test pressures) suspected

- Engineering models predicted max erosion depth = 0.09 inches

Key Flights

- Jan 24, 1985 (Flight 51-C, at 53°F):

- Severe erosion + blowby in primary O-ring, erosion in secondary O-ring

- Review acknowledged: “low temperature enhances blowby probability … condition not desirable but acceptable”

- Apr 29, 1985 (Flight 51-B, at 75°F):

- Nozzle-joint primary O-ring eroded 0.171 inches → never sealed

- Secondary eroded 0.032 inches

- Memo: “If same scenario in field joint … result would be catastrophe”

- June 1985 – Bench test of O-ring resiliency:

- At 100°F: O-ring maintained contact after joint rotation

- At 50°F: O-ring failed to reestablish contact

- Commission conclusion: O-ring resiliency directly related to temperature. Warm O-rings reseal faster; cold O-rings may not seal at all

- Aug 1985 NASA briefing:

- Stated “qualitative probability of secondary O-ring failure is high” if erosion penetration occurs after ~330 ms of ignition

Atmosphere Before Challenger Launch

- By Jan 1986, ample evidence existed:

- Field-joint rotation risk

- O-ring thermal distress (erosion + blowby)

- Low temperatures significantly worsened performance

- Teleconference discussions occurred under serious doubts about O-ring reliability in cold conditions

⚠️ Core takeaway: Before Challenger, both engineering tests and past flights showed strong warnings about O-ring vulnerability, especially at low temperatures. These warnings were known to NASA and Thiokol well before Jan 1986.

🚀 Section 3: Data Analysis for Field-Joint O-Rings

3.1 Model Fitting

Data Setup

- We have 23 shuttle flights with thermal distress data

- Each flight has 6 primary O-rings

- Outcome: number of O-rings showing thermal distress (erosion or blowby)

- Secondary O-rings: only 1 case of damage, so ignored in modeling

Modeling Framework

- Let X = number of distressed O-rings in a flight

- Assume Binomial distribution with probability depending on:

- Temperature at launch (t)

- Leak-check pressure (s)

- Probability of damage per O-ring: p(t,s)

- Logistic regression with temperature + pressure:

- Intercept: α̂ = 2.52

- Temperature effect: β̂ = -0.0983 (negative → higher temp = less damage)

- Pressure effect: γ̂ = 0.00848 (very weak)

- Goodness of fit: G² = 16.546 (20 df) → good fit

Dropping Pressure

- Pressure effect not statistically significant

- Temperature-only model:

- α̂ = 5.085

- β̂ = -0.1156

- G² = 18.086 (21 df) → also good fit

- Conclusion: Temperature is the key predictor

Visualization (described)

- At ~30–40°F: predicted ~4–5 of 6 O-rings distressed

- At >70°F: predicted ~0 O-rings distressed

Alternative Binary Model

- Defined binary outcome: 1 if ≥1 O-ring incident, 0 otherwise

- Logistic regression (temperature-only) → results similar to binomial model

- Interpretation: low temperature = high risk

3.2 Confidence Intervals

- Method: parametric bootstrap (Efron 1979)

- Findings:

- At low temps (<65°F): intervals wide (high uncertainty)

- At high temps (>65°F): intervals narrow (more stable)

- At 30°F: expected # incidents ~1 to 6 O-rings (uncertain but clearly dangerous)

3.3 Effect of Data Perturbations

- Sensitivity analysis: remove each flight one by one

- Key result: Flight 21 (75°F, 2 incidents) was highly influential

- Removing it shifted coefficients ~4 SDs

- Probability of such an event under model < 0.001

- But it was real → suggests unmodeled factors

- Even without Flight 21 → low temperature risk remains very high

🔑 Key Takeaways from Section 3

- Temperature is dominant factor; pressure negligible

- Logistic regression confirms: ~31°F → majority of O-rings expected to fail

- Uncertainty large at very low temps, but always points to high risk

- Flight 21 anomaly shows model is imperfect but doesn’t change conclusion

- Statistical evidence strongly supported engineers’ warnings before Challenger

🔎 3.4 The Form of the Model — Detailed Summary

Why check the form?

- Logistic model assumes:

- Logit link is correct

- Logit(probability) vs temperature is linear

- With only 23 points, authors preferred simplicity but tested linearity assumption

Testing Quadratic Term

- Quadratic term γ̂ = 0.0041 (not significant)

- Likelihood ratio = 0.494 (df=1), far below threshold

- No evidence of curvature → straight line is adequate

Nonparametric Smoothing Check

- Used Cleveland & Devlin (1988) smoothing with f = 0.4

- Smoothed curve ≈ logistic fit

- Conclusion: linear logistic model fits well

Residual Diagnostics

- Checked standardized residuals

- Outliers:

- Point 9 (smoothed = 0)

- Point 21 (anomalous influential flight)

- Otherwise: no evidence of systematic nonlinearity

Local Deviance Plots

- Compared local vs global deviance

- Fit adequate except large jump between points 14 & 15 (due to Flight 21)

- Removing Flight 21 → diagnostics still support adequacy

ACE Algorithm

- ACE (Breiman & Friedman 1985) checked transformations

- Found logit(probs) vs temperature ≈ linear

- Strong evidence logit link is appropriate

Pressure Variable Diagnostics

- Re-introducing pressure failed:

- Very few data points

- Only one case with incident at 50 psi

- Smoothing unreliable, Newton-Raphson unstable

- Conclusion: pressure cannot be modeled reliably

🔑 Final Takeaways from Section 3.4

- Linear logistic model (temperature-only) is adequate

- Nonparametric smoothing, residuals, and deviance checks confirm adequacy (except Flight 21)

- Logit link is appropriate, simpler and stable

- Pressure variable discarded as unreliable

👉 Bottom line: The Challenger O-ring data strongly supported a simple, linear logistic regression of failure probability vs temperature. The model was statistically sound, stable, and showed clear risk at low temperatures, despite one influential anomaly.